This post contains some gentle spoilers for The Peanuts Movie but none for Star Wars: The Force Awakens.

I don’t get super-excited about up-coming movies usually. My honest reaction upon being asked if I had seen the new Star Wars was to ask, “Oh, is it out already?” However, one movie that I have been mildly looking forward to is The Peanuts Movie. (Actually, in Australia its called, Snoopy and Charlie Brown: The Peanuts Movie but I’m not going to bother acknowledging that particular slice of ridiculousness beyond this bracket.)

I would not say that I am a huge Peanuts fan. However, I did read quite a few Peanuts collections when I was a kid (and they were probably decades old by then), which I remember enjoying sufficiently. And let’s be perfectly clear about this: “nostalgia” is the only reason this movie got made.

There is an interesting essay (with the rather click-baity title of “How Snoopy Killed Peanuts“) that claims that it was the development of Snoopy that saw Peanuts lose its edge:

Cuteness had replaced depth in a strip that had always celebrated the maturity and adult-like nature of precocious children.

Most of the strips that I read belonged to this earlier, darker time. I don’t wish to engage with that thesis other than to note that the assessment of the earlier Peanuts strips certainly matches how I understood Peanuts.

Although it is a new, separate thing, it is only natural that part of judging any adaptation is evaluating how well it encapsulates the spirit of the original. On the superficial level, The Peanuts Movie gets much of it right. The most obvious difference is the transition from a 2D comic strip to 3D animation. This works pretty well, and the key to its success is that the facial expressions are rendered in 2D. It sounds weird and it looks jarring at first but it effectively retains a significant amount of the original Peanuts look.

Beyond the animation, most of the iconic images get a look in: think Lucy’s psychiatry booth, Schroeder playing piano, Snoopy on his doghouse, etc. Similarly, homage is paid to the television specials with the distinctive Peanuts theme and the garbled, incoherent, off-key trombone-like voices of the adults.

All of this is quite an accomplishment, but one that could be more or less taken for granted in the twenty-first century (apart from the 2D expressions). However, the facet of Peanuts that stands out in my memory is its world-weary pessimism. (Once, when Charlie Brown is told that “you win some, you lose some” he responds dreamily, “Gee, that’d be neat.” [Okay, I’m just going to leave my misquote there because my memory of it was the important point.])

Peanuts Comic

In the strip, Charlie Brown lives in a universe where angst is just common sense and there is no reasonable expectation that anything will work out. So, I was very interested to see if this darkness made it into what was ostensibly a kid’s movie.

And it kind of does. Charlie Brown fails at virtually everything he turns his hand to throughout the movie, even when he has tried his darnedest and comes within moments of accomplishing anything. Charlie Brown has circumstances rail against him almost as often as his own ineptitude—an as near perfect expression of adulthood as you are likely to find. However, in the universe of the movie things do work out. Effort and perseverance are rewarded: albeit it only in the cinematic denouement. (Perhaps that is more the effect of translating nearly fifty years of comic strips into ninety minutes of popcorn upsell than anything else.)

It is not that the strip was an exercise in blatant nihilism, but it certainly presented hopes and dreams as a kind of cruel joke, and the movie, while not blatantly karmic, certainly seeks to reward an earnest heart.

The beginning is a bit purple but the style settles down soon enough. A singular work.

The beginning is a bit purple but the style settles down soon enough. A singular work. This starts exquisitely and even though it becomes more pedestrian as it goes on it remains enchanting right to the end. That is to say, it begins like a fairy tale but becomes a murder mystery/thriller too quickly. Still, I couldn’t put it down.

This starts exquisitely and even though it becomes more pedestrian as it goes on it remains enchanting right to the end. That is to say, it begins like a fairy tale but becomes a murder mystery/thriller too quickly. Still, I couldn’t put it down. It’s always difficult in magical stories to give the villains interesting and relatable motivations, and this book, while not perfect, comes as close as I have seen. The differing world views/religions of each of the major characters provides a meaningful basis for their actions. The author got the villains fully to “hatred/vengeance” but this would have been great if only they had pushed through to something more. But still, not a bad effort.This book did a good job of explaining itself as it went. Nearly all of the magical/supernatural elements were given sufficient explanations. As far as I can recall, there wasn’t any plot holes or logical inconsistencies that were waved away with “magic.”Maybe someone with more familiarity with Chinese myths would find this grating and over simplified but for me it was nicely done.

It’s always difficult in magical stories to give the villains interesting and relatable motivations, and this book, while not perfect, comes as close as I have seen. The differing world views/religions of each of the major characters provides a meaningful basis for their actions. The author got the villains fully to “hatred/vengeance” but this would have been great if only they had pushed through to something more. But still, not a bad effort.This book did a good job of explaining itself as it went. Nearly all of the magical/supernatural elements were given sufficient explanations. As far as I can recall, there wasn’t any plot holes or logical inconsistencies that were waved away with “magic.”Maybe someone with more familiarity with Chinese myths would find this grating and over simplified but for me it was nicely done. There’s a lot to like about this book. I particularly like the flashback structure being organised geographically. The three subplots are each allowed to end organically and still come together in a cohesive whole. Thematically the book is similar to “Tim Connor Hits Trouble” in that it is concerned with the increasing commerciality of life. TCHT is set in the Higher Education sector and deals with that in more detail, whereas this book deals with a wider range but with its most detailed description of the music industry. The aspect that I particularly like is that economic issues are only considered peripherally by the main character. The flashpoint of each subplot is the protagonist not understanding the aspects of economic reality that the respective antagonists have chosen to focus on. (The protagonist/antagonist description is not that accurate in all cases but you get the point.) A good read.

There’s a lot to like about this book. I particularly like the flashback structure being organised geographically. The three subplots are each allowed to end organically and still come together in a cohesive whole. Thematically the book is similar to “Tim Connor Hits Trouble” in that it is concerned with the increasing commerciality of life. TCHT is set in the Higher Education sector and deals with that in more detail, whereas this book deals with a wider range but with its most detailed description of the music industry. The aspect that I particularly like is that economic issues are only considered peripherally by the main character. The flashpoint of each subplot is the protagonist not understanding the aspects of economic reality that the respective antagonists have chosen to focus on. (The protagonist/antagonist description is not that accurate in all cases but you get the point.) A good read. This is a bit of an unsettling read. It doesn’t really start to come together until the poem in the middle. At first glance the plot seems to be a collection of events—both likely and unlikely—but it’s really quite a literal take on the process of personal reinvention.

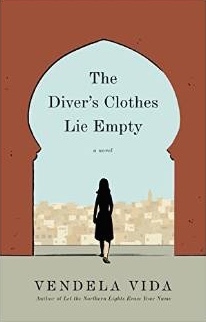

This is a bit of an unsettling read. It doesn’t really start to come together until the poem in the middle. At first glance the plot seems to be a collection of events—both likely and unlikely—but it’s really quite a literal take on the process of personal reinvention.